Read Jaye Weatherburn's account of sessions on Acquisition & Appraisal at iPRES 2017. Jaye attended iPRES 2017 with support from the DPC's Leadership Programme which is generously funded by our Commericial Supporters.

Thanks to a DPC Leadership Program scholarship (made possible by Commercial Supporters Arkivum, Preservica and Mirror Web) I attended iPres 2017 in Kyoto. This blog post focusses on the three presentations in the “Acquisition & Appraisal” session (Wednesday 27th September, 1410-1510). Each of the three presentations in this group focused on very different areas, from legacy media to augmented reality games, and also featured email analysis software. Each presentation had at its core the desire to provide answers to some digital preservation challenges, while also generating avenues and ideas for future research. I’ve gone with a descriptive style for my report on these sessions, with a wee bit of personal reflection.

The three presentations were:

- A Case Study on Retrieval of Data from 8 inch Disks ‒ Of the Importance of Hardware Repositories for Digital Preservation

- ePADD: Computational analysis software enabling screening, browsing, and access for email collections

- Challenges in Preserving Augmented Reality Games: A Case Study of Ingress and Pokémon GO

1. A Case Study on Retrieval of Data from 8 inch Disks ‒ Of the Importance of Hardware Repositories for Digital Preservation | Denise de Vries, Dirk Von Suchodoletz and Willibald Meyer.

First up, Denise de Vries and Dirk Von Suchodoletz took us on a journey detailing the many time consuming and difficult challenges involved in trying to get information off 30-year old, 8-inch magnetic floppy disk media, over many stages of a three-month period.

The brief given to them reads like the beginning of a detective story:

There is a set of 8-inch disks from early- to mid-1980s which contain research data. These data are required for current research. Retrieve the files from the disks and make them available on current media.

At the start, they didn’t have much information about the disks, and asking around wasn’t helpful, an all-too-common scenario when too much time has passed and inadequate documentation has been maintained for research data. In this case, there was no one around anymore able to share what systems were used back in the 80s when the disks were in use. As Dirk stated: this situation shouldn’t have happened, but it will keep happening (one slide had a great line to illustrate this point: "the plethora of common to weird storage media is still out there"). Denise and Dirk also talked about the role of hardware repositories for digital preservation, noting that for interpretation, the whole hardware-software stack needs to be considered. Because recovery of data from obsolete media is often costly and difficult, they presented a strong reinforcement of decades-old calls to preserve hardware, software, and the required documentation to use and understand them, possibly in “centres for the transfer of born-digital artefacts to current media which are hubs of expertise and resources” (p. 9).

My main takeaway from this presentation is reiteration of the fact that to connect, power, and set up working systems for reading and recovering obsolete media and data requires lots of expertise, know-how, problem solving abilities, scavenged and repurposed equipment, and lots of time. World-wide knowledge is available to help deal with complex problems like the ones this case study presents, and collaboration and cooperation are essential for success. This useful case study features many lessons learned for any others needing to attempt recovery of data from 8-inch magnetic floppy disk media.

A question that remains in my mind is: how much time could we save in the future if we can at least get the basics of preservation planning for research data in place now, from the beginning of their creation? This is not a new thought in the digital preservation community, but it is one that I will be taking back to my institution with renewed fervor. This case study is a great example highlighting that good, robust research data management now is one element that will help to avoid time-consuming and expensive forensic recovery missions in the future.

For more info on the background and origin of this project, check out Dirk’s Open Preservation Foundation blog.

2. ePADD: Computational analysis software enabling screening, browsing, and access for email collections | Josh Schneider, Peter Chan, Glynn Edwards and Sudheendra Hangal.

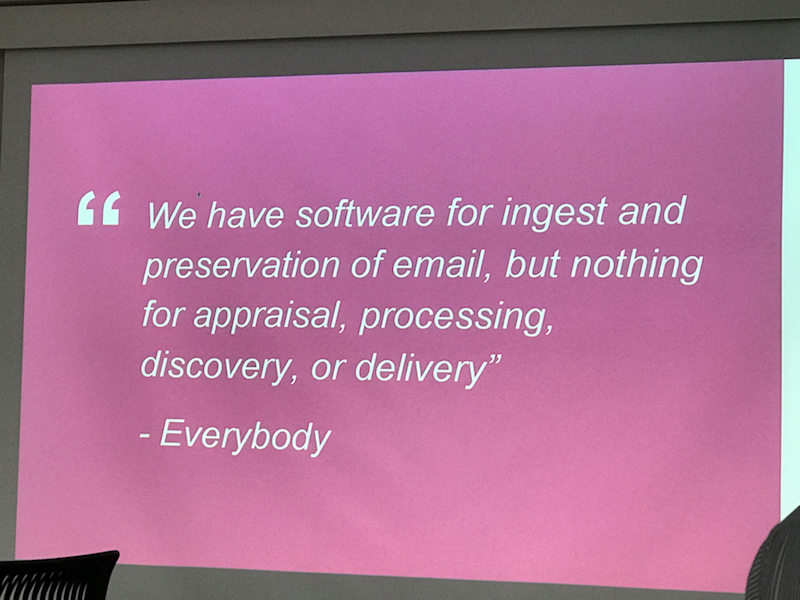

The exuberant Josh Schneider took the stage next, with a problem statement slide clearly showing the need for ePADD, which was developed by Stanford University's Special Collections & University Archives to help memory institutions appraise, collect, and make available email with cultural historical value. ePADD is open source software, available for Mac and Windows operating systems, and compatible with the Chrome and Firefox browsers.

ePADD has 4 modules: appraisal, processing, discovery and delivery. The “name resolution” functionality can recognize multiple email accounts as belonging to one person. The workflow for using ePADD is flexible - you don’t have to do curation at the beginning, and can move it through to the next module whenever you want.

Josh mentioned the “really intense” advanced search capabilities – you can search across entities, textual terms, any actions on email messages, and date ranges. Stanford University’s Special Collections & University Archives have a demonstration where you can browse through examples of the Harrison papers (documenting the life and work of eco-art pioneers Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison) or the Robert Creeley collection (American poet and author). While message content is redacted for privacy reasons, it gives a good sense of the functionality and use that ePADD can be put to for email collections.

Josh stated that building a robust community to support future development of ePADD is important to the team. They aim to continue with community building efforts, encouraging growth and participation. Phase 2 goals for ePADD development include: scaling up to be able to handle 750,000 emails on a modest computer setup, and various feature enhancements.

Download ePADD here or check out the Community Forums.

3. Challenges in Preserving Augmented Reality Games: A Case Study of Ingress and Pokémon GO | Jin Ha Lee, Stephen Keating and Travis Windleharth.

The final presentation in the session was from Jin Ha Lee, sharing a study of the challenges involved in preserving augmented reality games (ARGs). ARGs are games that blend the virtual world and real world via gameplay. Attempting to preserve everything that makes these games what they are remains a complex and challenging undertaking.

Two case study games were detailed: Ingress and Pokémon Go. Ingress is a location-based mobile game (2012, Niantic) – the goal of the game is to capture as many portals as possible for your team to control the most area. Pokémon Go (2016, Niantic) uses a mobile device’s GPS to move the player’s avatar in a virtual world as they navigate in the real world to capture Pokémon characters, and also to “raid” (take down difficult bosses).

Because of the social, real-world components involved in these games, challenges arise as the virtual game world by itself is not enough to preserve – we also need to ask: what of the real world social gameplay is essential to capture to understand the full reality of the game; how much of the real world gameplay elements are preservable; and what format should they be preserved in? Social gameplay that happens outside the game needs to be understood and identified, in order to document it. Such “metaplay” and its context is not recorded in the game itself, but needs to be, as such actions and decisions outside the virtual reality of the game can have huge impacts on the game’s direction and outcome.

Jin Ha Lee stated that her background is not in digital preservation, and that she came to iPres to learn from the digital preservation community to better understand the solutions to these challenges, and to work together on the problems. This collaboration element between people from different backgrounds is one reason I find iPres conferences so interesting and useful.

Preserving the seemingly intangible metaplay that takes place in ARGs – to be able to capture and re-present groundbreaking social events such as the phenomenon that was Pokémon Go in 2016 through time for future audiences, is an exciting challenge for the digital preservation community. Future research for this team includes detailed investigation to determine the significant properties for ARGs.

The three papers for this session aptly offer an overview of current challenges and some solutions in different areas of focus for digital preservation efforts, leaving much room for further exploration.